Topkapi Palace wasn't built in a day - or even a decade. Over 400 years, successive sultans added their personal touches, creating an architectural layer cake that tells the story of the Ottoman Empire's evolution from medieval fortress to Renaissance palace to baroque excess.

🏰 Phase 1: The Conquest (1460s-1470s)

Builder: Mehmed II (Mehmed the Conqueror)

Style: Early Ottoman / Byzantine-influenced fortress

The Original Vision

When Mehmed II conquered Constantinople in 1453, he needed a palace that announced: "The Ottomans are here to stay." He chose a strategic hilltop overlooking the Golden Horn, Bosphorus, and Sea of Marmara - the exact spot where Byzantine emperors once held court.

Key features from this period:

- The Imperial Gate (Bab-ı Hümayun): Massive and fortress-like, designed to intimidate. Notice the thickness of the walls - this was as much defensive structure as ceremonial entrance.

- First Courtyard layout: Inspired by Byzantine imperial complexes with separate zones for military, administrative, and private quarters

- The Tiled Kiosk (Çinili Köşk): The only surviving pavilion from Mehmed's era, now a museum. Its simple tile work contrasts sharply with later extravagance.

Why it looks "simple"

Mehmed was more warrior than aesthete. The early palace was functional: thick walls, small windows, minimal decoration. The message was power through strength, not beauty.

🎨 Phase 2: Classical Ottoman Perfection (1520s-1560s)

Builder: Süleyman the Magnificent

Architect: Mimar Sinan (the Ottoman Michelangelo)

Style: Classical Ottoman

The Golden Age

Under Süleyman, the Ottoman Empire reached its zenith, and the palace reflected this confidence. This is when Topkapi became truly magnificent.

Sinan's contributions:

- Perfect proportions: The Third Courtyard's buildings follow mathematical harmony - each element relates to the others through geometric ratios

- The Audience Chamber: A masterpiece of negative space - the room feels larger than it is through clever use of height and light

- Süleymaniye elements: Notice similarities to Sinan's mosques: domed roofs, columned porticos, cascading structures that create visual rhythm

The İznik Tile Revolution

This period saw İznik pottery reach its peak. The distinctive blue, turquoise, and red tiles weren't just decorative:

- Technical marvel: Required firing at exact temperatures (920°C) to achieve that luminous glaze

- Color symbolism: Blue represented heaven, red was earthly power, white symbolized purity

- Pattern language: Tulips (Ottoman imperial symbol), carnations (paradise), cypress trees (eternity)

Best examples: Circumcision Room (1640s, but using Süleyman-era techniques) has the finest surviving İznik work in the entire palace.

🌟 Phase 3: Baroque Influences (1703-1730)

Builder: Ahmed III

Style: Ottoman Baroque / Tulip Era

The Tulip Period

After centuries of military expansion, Ahmed III turned inward, creating a pleasure palace. European baroque styles began influencing Ottoman design.

The Library of Ahmed III (1719):

This is where traditional Ottoman and European baroque collide:

- Marble arcade: Classical Ottoman proportions

- Curved lines: Baroque influence from France

- Fountain integration: Uniquely Ottoman - water as architectural element

- Mother-of-pearl inlay: Reaching new levels of delicacy

What changed?

- Lighter, airier spaces: Larger windows, more glass

- Curved forms: Baroque flourishes instead of straight Ottoman lines

- Decorative excess: Gold leaf, mirrors, European-style painting

- Garden integration: Pavilions opened to elaborate garden designs

🌊 Phase 4: The Fourth Courtyard (15th-18th centuries)

Multiple builders

Style: Eclectic mix evolving with each sultan

A Palace Within a Palace

The Fourth Courtyard is the most architecturally diverse section. Each kiosk tells a different story:

Baghdad Kiosk (1639)

Built by: Murad IV to celebrate conquering Baghdad

Style: Classical Ottoman with Persian influences

- Octagonal plan (Persian garden pavilion tradition)

- Extensive use of mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell inlay

- Dome with intricate painted patterns

- Stained glass windows filtering light into jewel-toned patterns

Revan Kiosk (1636)

Built by: Murad IV (he liked building victory kiosks)

Style: Classical Ottoman

- Cruciform plan with domed ceiling

- Some of the finest İznik tiles in the palace

- Built entirely of marble - a show of wealth

İftariye Pavilion (18th century)

Purpose: Breaking Ramadan fast

Style: Late Ottoman

- Golden gilded interior (hence the nickname "Gold Kiosk")

- European rococo influences in decoration

- Designed for spectacular views over Bosphorus

🏛️ Architectural Elements Explained

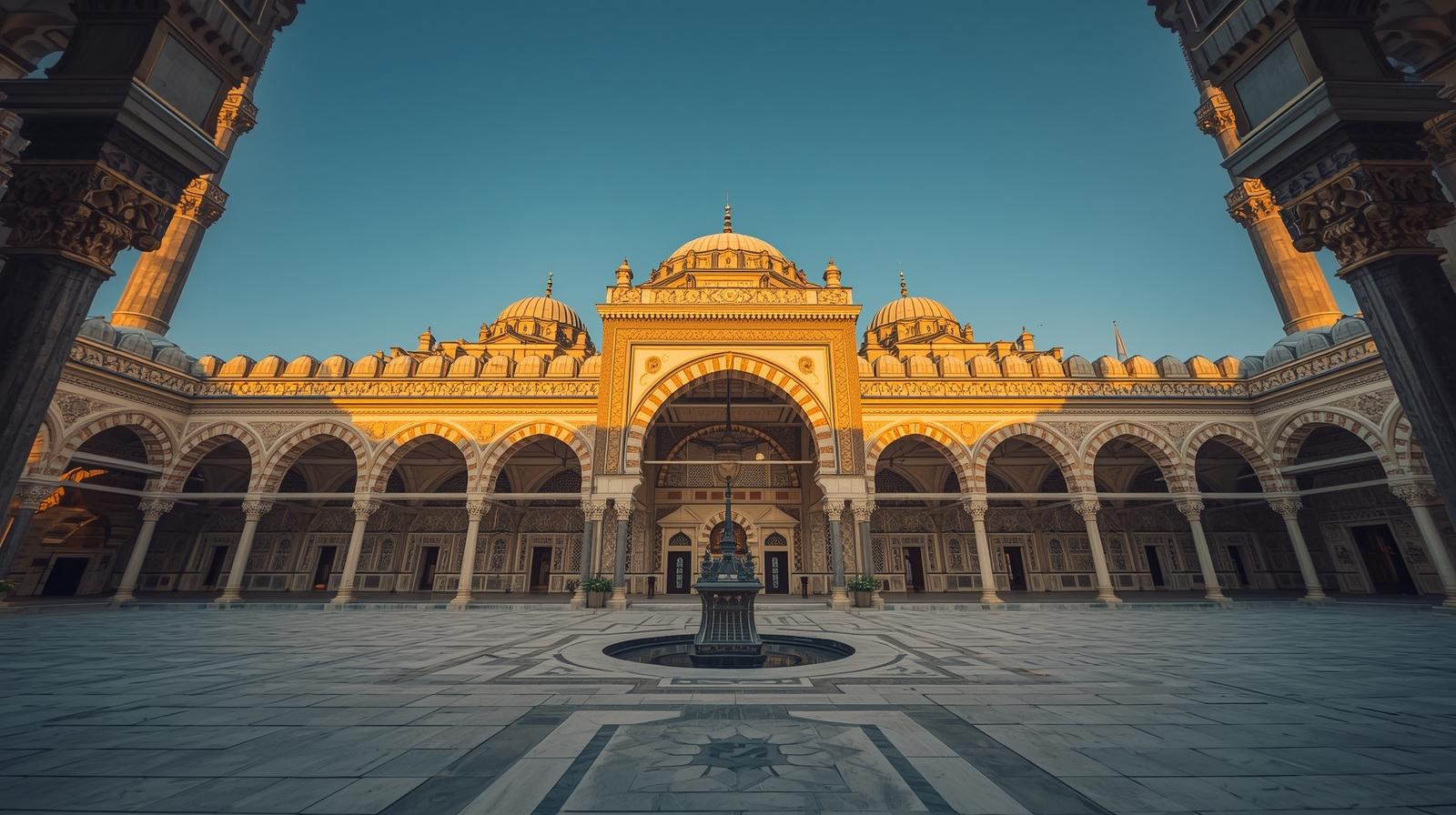

Why So Many Courtyards?

The progression from public (First Courtyard) to private (Fourth Courtyard) reflected Ottoman power structure:

- First Courtyard: Anyone could enter - service areas, guards, administrators

- Second Courtyard: State officials and dignitaries - the business of empire happened here

- Third Courtyard: Only the Sultan's inner circle - throne room and royal chambers

- Fourth Courtyard: Sultan's private retreat - family and favorites only

The Dome Obsession

Ottomans inherited Byzantine love of domes but pushed engineering further:

- Weight distribution: Arches channel weight to columns and walls

- Height illusion: Domes painted with sky patterns made ceilings feel infinite

- Acoustic properties: Domed rooms had perfect sound for music and recitation

Those Overhanging Eaves

The distinctive deep eaves (saçak) serve multiple purposes:

- Protect walls from rain (preserves precious tiles and paintings)

- Create shaded zones in courtyards

- Channel rainwater away from foundations

- Visual signature - you can spot Ottoman buildings from these alone

🔍 Spot the Details

The Tughra (Imperial Monogram)

Look for ornate calligraphic signatures throughout the palace. Each sultan had a unique tughra incorporating their name and title. Finding which sultan built or renovated a section is as simple as finding his tughra.

Window Placement = Status

- Large windows: Public or semi-public spaces

- Small windows high up: Harem and private areas (privacy + ventilation)

- Screened windows (kafes): Women could see out; no one could see in

Floor Levels Tell Stories

As you move through the palace, notice floor levels change. Each courtyard is slightly higher than the previous - physically climbing toward the Sultan's presence.

🏗️ Building Techniques

The İznik Tile Process

- Mine quartz from hills near İznik

- Grind to powder, mix with lead and tin oxides

- Paint design on white glaze

- Fire at 920°C for 48 hours

- Result: Colors that have lasted 500+ years without fading

Why they're irreplaceable: The exact recipe was lost when İznik workshops closed in the 1700s. Modern reproductions can't match the original luminosity.

The Wooden Ceilings

Many ceilings are timber, not stone:

- Earthquake resistance (Istanbul is in a seismic zone)

- Easier to paint and decorate

- Faster construction

- Can be replaced without affecting structural integrity

🔧 Modern Conservation Challenges

Preserving 500-year-old buildings is complex:

- Climate control: Turkey's humidity damages tiles and wood

- Visitor wear: 3 million feet per year = erosion of marble floors

- Lost techniques: Finding craftspeople who can repair İznik tiles properly

- Seismic reinforcement: Adding earthquake protection without damaging originals

🎓 Why This Matters

Topkapi isn't just beautiful - it's an architectural time capsule showing how an empire evolved from medieval fortress mentality to Renaissance sophistication to baroque excess, all while maintaining distinct Ottoman identity.

When you visit, you're not just seeing a palace - you're reading 400 years of history in brick, tile, and marble.

Guided tour recommendation: The palace offers architecture-focused tours twice weekly. Worth it - guides point out details you'd miss, like subtle Persian influences or recycled Byzantine columns.